To paraphrase E.H. Gombrich, there is no such thing as (Video) Art there are only artists (who use video). For every group of artists who are willing to struggle to express or communicate something with the television technology that already exists, there are odd individuals with strong creative visual imagination whose vision stretches to the possibilities of a new technology beyond that developed for the needs of broadcasting, surveillance, etc. These people recognise the possibility for visual instruments that may be played in the same way that musical instruments are played, but someone has to get down to building them.. For good or ill most artists do not happen to be electronics engineers, nor are most electronic engineers artists. But over the years in scattered parts of the world enough hybrid individuals or collaborative groups have emerged willing and able to take the plunge and help these dreams materialize. As a result a range of instruments has been built which give birth to new visual forms which are a strong departure from the conventional pictorial realities and limited ‘special effects’ which dominate the world’s television screens. (How the serious artist working with video gets to hate those words ‘special effects’ – no one presumes to call Picasso’s paintings by such a term just because they do not conform to our ‘normal’ view of reality!)

For a picture to appear on a television set there must first be an electrical signal with certain conventional properties (like its size, timing, etc.) which allows the television set to accept it and display an organized image. It is conventionally assumed that such a signal originates from a television camera, and that this camera is designed and aligned and pointed at the `real’ world to give an (approximately) accurate representation of that world. There are many visual artists, of which I am one, who reject both these notions as being an unnecessary limitation on man’s creative imagination and expression and on the television medium itself. It is not necessary to use a television camera in order to arrive at the electrical signal which forms meaningful images on a television set. We can for example achieve this result by direct synthesis of that signal.

Nor is there any human law which insists that television cameras give an accurate representation of -the world as we normally perceive it. It is true that they have largely been designed to mimic normal human ocular perception, but to restrict them to this mode for all purposes is to deny the enormous visual possibilities they have for showing us the world in different ways. Some people may well say at this point ‘Why bother?’ but there are always those who are shut off to the riches that art proclaims. It is perhaps worth noting at this point that video signals may be projected directly onto a screen without need for television sets at all, This rather deflates the theories of certain academics in this country who have tried to define an aesthetic based around television cameras, monitors and video tape recorders. Video can exist happily without any of them! The prime aspect of video is the electrical signal and those artists who have been involved in technical innovation concentrate their attention on the possibilities inherent in its formation and manipulation. This craft relationship becomes fused with the inner needs of the artist and audience via the work produced on the new instruments.

There are several types of technique developed by artists to achieve the images they require on television screens. Many of them do overlap with techniques developed by commercial engineers for broadcasting needs and there is probably a degree of influence and interaction between the two groups. Many artists are abreast of the latest engineering developments and the new possibilities opened up by the fast develop micro-electronic circuits, digital computer techniques, microprocessors, etc. Also many design engineers watch what artists are doing with both the ‘traditional’ equipment and the new instruments that have been developed.

There are basically four areas that artists have developed in their need to utilize the television screen as a canvas (for this categorization see the article by Stephen Beck in Video Art). These are:

1. Camera image processing

2. Direct video synthesis

3. Scan modulation or re-scanning

4. Non recordable manipulations.

This is a useful categorisation which covers pretty well the activities of artists who have engaged in the development of video instruments for their own and others’ use. Let us go into these various areas in more detail.

There are various traditional camera manipulations available in most television studios: cutting and mixing between television cameras for example; also the generation of wipe patterns as a means of transition; and often some simple colourisation intended for titling, but often of very restricted range. But much more is possible, including sophisticated colourisation either by tinting monochrome images or altering the colour balance of colour images; colourisation by quantizing an image into various levels of grey and colouring each level independently; keying either by luminance information from a monochrome image or chrominance information from a colour image and inserting different images into various parts of other images; modification of images from positive to negative; generating edge effects around lines of contrast change; cutting and mixing between images in nonstandard ways, etc. Many of these effects are available on conventional studio vision mixers, but artists have had specific reasons for developing their own particular instruments (see later in this article). My own Videokalos lmage Processor falls into this category. Dan Sandin in Chicago has also developed an equally sophisticated though less compact system which is often used in conjunction with Tom DeFanti’s digital computer graphics system called GRASS. Several other systems have been built over the past years, mainly in North America.

2. Direct video synthesis

This category includes instruments which have been developed to produce images without any need for television cameras, although many of them do process camera images as well to some extent. Without going into too many technicalities the basic principle is to use electronic signal generators coupled to signal processors to form meaningful images. For example, signals may be generated to give points, lines and colours which together form coloured patterns. These patterns could then be made to move by modulators or oscillators or even audio signals, and could be changed in size or colour shading by further amplifiers. The aesthetic of such devices tends towards the geometric, and they often have combined into them elements from category 1. Instruments of the direct video synthesis group include Chromaton by BJA Systems, Stephen Beck’s Direct Video Synthesiser and Richard Monkhouse’s Spectron (for EMS) and Videosizer (for Ludwig Rehberg).

There is another group of instruments within this category, and which overlaps into the next, which should be described as computer animation. This process imitates the procedures of film animation and is still usually photographed from the television screen frame by frame by a film animation camera with the result being film. It is technically just possible to do this directly onto videotape which is why it is included here. Basically the television screen is used to display a computer generated picture which acts like the acetate cell of the animator. Much time can be saved by the computer being able to interpolate between images, colour in large blocks etc, but such systems are very expensive and no individual artists to my knowledge have developed their own systems. More easily one can use a cathode ray tube as a display for computer generated abstract patterns which can be film-animated as above, or changed in real-time and observed by television cameras. This overlaps into our third category.

3. Scan modulation or re-scanning

There are basically three variations here, involving a normal television camera (usually monochrome, viewing (a) an oscilloscope or computer visual display unit, (b) a television screen carrying a blank raster, or (c) a television screen carrying an image derived-‘ from a second camera or some other source. However it is

first derived, the image being viewed may be modified by two means: either by computer programme and normally displayed, or by geometric manipulation of the display screen itself. This deflection modulation may be achieved by magnetic or electronic means. If a blank raster is used, lissajous patterns result. If an image is used, distortions of a particular nature due to scan conversion are the result. It should be noted that a normal camera is used to observe such distortions in order that the final signal conforms to the normal pattern required for recording. This signal may of course be processed as in category 1.

The various systems developed may or may not have the re-scan camera built into them. Examples of type (a) are Tom DeFanti’s previously mentioned computer system GRASS and Richard Monkhouse’s oscilloscope pattern generator Quartic. Examples of (b) and (c) are the systems of Paik/Abe and Rutt/Etra in North America.

4. Non-recordable types

Any of the last category examples would serve here if there were no re-scan camera to convert the manipulations and distortions into a normal recordable signal. Many artists have used ‘prepared television sets’ or even simply faulty ones as part of their work in gallery displays and of which there is no permanent record. On the whole technical innovation in this area has not led to the development of new instruments.

All the instruments developed in the above categories may be divided into two basic types. Either they are primarily designed for real-time operation like a musical instrument, or they are best used to create images that are edited together to form a cohesive whole. In the UK at least, and probably in North America too, there is a strong tendency towards the former aesthetic as it embraces both possibilizties and is becoming more possible as electronics and design experience grows.

Personal involvement

My own particular involvement as an artist with technical innovation should serve as an interesting example, and is the one I am best qualified to write about. Whilst studying film and television at the Royal College of Art in London I was fortunate in having access to an ex-broadcast colour television studio. I was at that time interested in the relation of music and sound to the picture area, and in particular with the relationship between electronic music and electronic (television) imagery. I was also involved with the equivalence between music as an abstract aural phenomenon (not taken from the natural world but invented by men and their instruments), and television images as an abstract visual phenomenon (most ‘normal’ television images are derived from the natural world, although with man-made instruments). This involvement has continued to this day. Armed with these notions, I entered the colour studio. I should perhaps add that I had also at that time constructed a crude but effective physical device for transposing sound into a visual pattern. I soon discovered that from the remote camera control unit of a broadcast colour television camera one could control the colours and density of the image perceived by that camera. As all the camera control units for the studio’s four colour cameras were situated side-by-side in the engineering control room I realized that one could colour the four images as one chose from the one location. Unfortunately the way to mix or cut between these cameras was on the vision mixer in the traditional ‘director’s’ control room, so I broke with normal studio practice and ‘directed’ the vision mixer (a person that is) from the engineering control room rather than from the traditional place alongside them. This proved to be no problem as most other ‘effects’, such as chroma-keying, could equally be controlled from the engineering position. I thus began to use the studio as an expensive electronic colour paintbox. The screen became a canvas upon which I could paint colours using images derived from the cameras (see category 1).

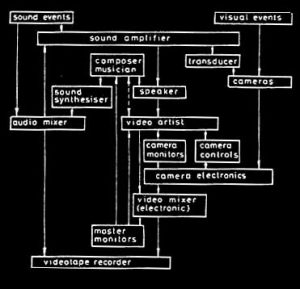

Video, and television in general, has the important quality that one can see exactly what one is doing on the screen as one does it, with no guessing. It is fundamentally different from film in this respect. With film it is ultimately a (professionally trained) guess as to exactly what is on the film, and it certainly does not allow the incredible flexibility of manipulation of the image in real time as television does. I was working in conjunction with live performance electronic music at that time and it very quickly became apparent that there was a direct analogy between musical instruments and the way I was working visually with the television studio. With a musical instrument one, say, plucks a string and immediately receives aural feedback of one’s hands’ action on the instrument. With, say, the television camera control one turns a knob and immediately receives visual feedback of one’s hands’ action on that instrument. The composer/musician and myself soon developed an aesthetic utilizing all these techniques whereby we created non-representational video programmes by recording real-time performances recorded directly onto videotape, he playing his instruments and watching my visual output on a television screen and I playing the studio instruments and listening to his aural output on loudspeakers. A diagram of this situation shows the arrangement schematically:

There are several small points of interest. We found we could produce videotapes without any need for editing and with just four people: myself, the musician/composer, a vision mixer and the studio engineer. In particular no camera crew was necessary. l should also note that my “performance” on the studio cameras resulted in their being totally misaligned from their normal function of accurately reproducing the ‘normal’ world around, and some time had to be spent later re-aligning them.

Having left the college and finding I could only occasionally raise the finance to return to continue this work in an expensive broadcast-type television studio I realised I had been in a privileged position there, but long enough to have learnt some important lessons. No such experimentation seems to have been possible within the broadcasting institutions themselves, for, despite the better equipment, the cost of utilizing it in this way and the rigid demarcation of people’s roles prevented such an informal searching approach. It was obvious that there was a real need to develop a video instrument, analogous to a musical instrument, that would allow me (and later others) to perform the same functions I had been doing in the colour studio, but without the need for so much expensive equipment. What was really needed was a specially built image processor that would allow the functions of complex colourisation, keying and vision mixing in the same console, preferably utilizing cheap monochrome cameras as inputs.

The idea was thus born to build an instrument. I had no knowledge of electronics personally and had no contacts or knowledge at that time with what was happening in North America. Fortunately though I crossed paths with a wonderfully inventive and enthusiastic self-trained electronics designer called Richard Monkhouse who was himself very keen to develop abstract television imagery. He had almost single-handed designed and built Spectron, a complex though somewhat unwieldy digital direct video synthesizer (see category 2) whilst working for EMS. This instrument could produce complex patterns of images without need for a video camera (though it could also be used in conjunction with one). I approached him and he was enthusiastic about the concept and my building my envisaged instrument! I will cut short here a long story of personal endeavour, frustration, tears and expense and enormous demands on Richard’s tolerance to say that after about eighteen months the prototype was complete. I suppose one could say he designed the circuitry (from my concept of what was needed), I somehow built it and he then got it all to work (though all these processes went through many stages for each section of the instrument).

Basically what we ended up with was a portable self contained unit, physically modelled on Spectron which performed the following functions: colour sync pulse generation with genlock; five independent inputs of monochrome or colour signals, each of which could be independently colourised or altered positive/negative; three independent keys operating in a luminance or chrominance mode; 22 x 22 hole patch board for rapidly inserting any signal within the instrument into one side or other of the keys; and an eight channel four bank ABCD mixer/switcher with independent fade to black on the AB and CD banks (AB banks give a composite PAL encoded output capable of direct recording onto videotape whilst the CD bank output is left in an RGB mode – three outputs, one for red, one for green and one for the blue signals. This is used for previewing or for other effects manipulation external to the machine).

So many people thought that there would be a small market for such an instrument that we decided to go a stage further at this point in order to build a fully professional version, properly engineered for purchase by third parties and with all the electronics on printed circuit boards for reliability and in a sturdier case. Certain other refinements were added at the production stage, such as a wipe pattern generator, a colour bar generator to allow the instrument itself and external equipment to be lined up to a common standard, and an integral encoder switchable between PAL and NTSC colour standards. An RGB output is also supplied for SECAM users (one of the first built was supplied to a studio in Paris).

The end result of this process, then, is a fully portable self-contained instrument generating all the pulses necessary for driving a colour television studio and providing an extremely complex manipulation of video source inputs (usually cameras, but other synthesizers could also be connected) in real time. It should be noted that it is entirely an analogue device, giving totally different effects to the digital processors now beginning to appear, and it maintains its great flexibility by operating throughout on a separate RGB principle rather than on encoded signals. Only the output needs to be encoded. It seemed sensible to build an instrument that could be used anywhere in the world on any television standard and with any mains electricity supply, so this we did. The sync pulse generator is also switchable from PAL to NTSC; SECAM shares the PAL pulses, only the encoding system is different. Although priced so that any small studio could afford it the instrument will interface with broadcast equipment and video processed through it has been broadcast by the BBC.

Designing and building the professional version engaged me in the acquisition of new skills, in particular that of designing printed circuit boards from the drawings of electronic circuits provided by Richard, which I picked up largely by trial and error (and a few more tears along the way). The advantages of a professional version over a hand-built one are the enormous increase in reliability and the potential to interchange sections should faults ever occur.

I hope this gives an illustrative account of how an artist might get involved in technical innovation and how, once started by some catalyst or other, the ideas develop as an interchange between what is technically possible and what sort of artistic control one seeks. The need in my case was for a portable instrument giving maximum real-time control over the colours and forms possible on a conventional television screen. The instrument itself once built then generates possibilities one had not at first thought of and which get integrated into the on-going development of one’s creative work. This is really a totally traditional process in the arts between expressive needs and one’s grasp of the techniques or crafts of one’s medium, between content and form and the means to achieve both. In my view the great majority of good artists are good craftsmen in their medium and the craft aspect of video requires at least some understanding of the electronic substance of the television medium if not the extreme of actually designing circuits and building things.

This is a very exciting time historically in that the rapid advances in electronics are allowing the development of new instruments in both fields of music and visual events. There is some criticism along the lines that electronic sound synthesisers, for example, produce a crude recognisable sound and do not integrate well with their human operator. Well, all instruments have their own particular ‘sound’ which is based on their harmonic structure (or lack of it), and as for the other criticisms we should remember that it is very early days yet compared with the hundreds of years over which most instruments have developed. I for my part am aware that the ‘feel’ of an instrument is very important to the overall pleasure one must gain from playing it and I incorporated this element into my design.

My philosophy as an artist also differs radically from that of the designers of much highly expensive equipment designed primarily for broadcast users. A good example is the present generation of digital devices that store a frame or frames of a television picture and allow for certain manipulations of that frame. These devices, costing upwards of ten times my image processor, have finite operations that can be quickly learnt by any operator. I believe that instruments should be maximally open-ended in their possibilities and that human skill should add significantly to those possibilities that are inherent in the technology of the instrument, i.e. the more skill one acquires in operating my image processor the better the final perceived image becomes. If an instrument can also be open-ended technically (as mine is by accepting multiple inputs from any other source one can imagine) then so much the better. The only real problem would arise if television switched to being an all digital affair, or the television display changed its standard radically (to give higher resolution etc). Either of these possibilities might occur in the future, though unlikely to happen quickly, and would involve radical re-design.

One can see that the philosophy with which an artist utilizing video approaches his medium is likely to be very different from the design philosophy of most engineers and television producers. The artist starts from the premise of what he would like to do rather than what is possible in the current technological condition. He wants devices that give maximum personal control over the medium rather than having to give instructions to other people to do things. And he may well have a wider vision of what is visually acceptable, technically, than most engineers and also of what is acceptable, in terms of human meaning and relevance, than most television producers working in broadcasting. Artists are making significant technical as well as aesthetic advances in the development of the video medium.

Reference

1. Beck, Stephen. ‘Image Processing and Video Synthesis’ in Video Art, Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch, 1976.